Elizabeth Whitlow of Texas History Research Services has compiled a brief history of Enfield in conjunction with the 100th Anniversary of the original plat of the neighborhood.

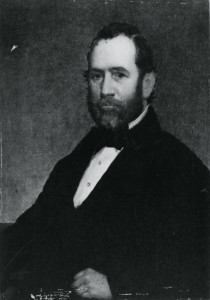

At age 22 in 1834, Marshall Pease left his “unprosperous” life at home in Enfield, CT to look for opportunity. He found it in Texas. He arrived in time to participate in the first battle of the Texas Revolution at Gonzales. He read law at Mina (Bastrop) and participated in government in the new Republic, writing part of the Constitution and later, part of the criminal code. He was a successful lawyer in Brazoria, elected to the legislature, and then as governor in 1853. Before and during his two terms he was widely respected for his intelligence, hard work, and sound judgment. Gov. Pease’s most outstanding accomplishment was settlement of state debt from the Revolution, finally putting Texas in sound financial condition. He established the permanent school fund and worked to bring vital railroads to Texas. He supervised a campaign that lead to completion of the Governor’s Mansion, General Land Office, and a new Capitol.

Marshall Pease married his second cousin Lucadia Niles of Poquonock, CT. Their children were Carrie, Julia (Julie) and Anne (who died as a child). The family moved from the new Governor’s Mansion to the nearly identical Woodlawn, where they lived through Civil War years that were hard on both sides in the conflict. As a Union sympathizer, his life was sometimes threatened and his property would have been confiscated if he left town. After another period as Governor following the War and later work as an Austin lawyer, Marshall Pease died in 1883.